About Tea

WHAT IS TEA?

When we talk about tea, we basically mean a drink made from the leaves of the tea bush Camellia sinensis. It is the same plant whether the tea becomes white, green, oolong, black or pu-erh – the difference lies in how the tea is grown, harvested and processed after picking.

In addition to this there are other plant-based drinks that are often called “tea” in everyday language – rooibos, herbal blends and fruit infusions – but they are not classified as tea in the botanical sense.

Tea is often considered the world’s second most consumed drink after water, with long traditions in China, Japan, India and many other countries.

THE ORIGIN OF TEA AND ITS LEGENDS

The origin of tea is found in China, and many legends have grown up around it. One of the most famous stories tells of the emperor Shen Nong who, according to tradition in 2737 BC, had some leaves fall into his boiling water by accident – and liked the taste.

Historically, we know that tea has been used in China for at least 2 000 years, even if the legends about its origin are much older. During the Tang and Song dynasties, a sophisticated tea culture developed with its own brewing methods, vessels and ceremonies. Tea then spread to Japan, Korea and later to India and the rest of the world.

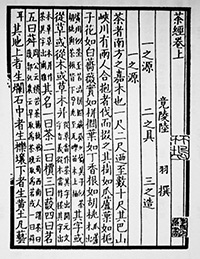

THE FIRST BOOK ON TEA – LU YU AND CHA JING

Much of what we know about early teas comes from the first known treatise on tea, Cha Jing – “The Classic of Tea” – written by Lu Yu (733–804) during the Tang dynasty.

Lu Yu grew up among Buddhist monks, became deeply interested in tea and devoted his life to studying its cultivation, production and preparation. In Cha Jing he describes tea bushes, regions, processing methods, water quality and tea ceremony. Several of the Chinese tea types still produced today have roots going back to this period.

OXIDATION AND “FERMENTATION” – WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE?

When we talk about different colours and styles of tea, much comes down to oxidation – an enzymatic reaction where compounds in the tea leaves react with oxygen when the cell structure is broken. This is what makes tea range from light green to deep dark.

In older tea circles the word “fermentation” is sometimes used for this process, which easily causes confusion. For most teas this is not fermentation by microorganisms, but oxidation in contact with air.

True microbial fermentation occurs mainly in some dark teas – for example Shu Pu-erh and other Hei Cha – where microorganisms play an active role during ageing.

MAIN TYPES OF TEA – OVERVIEW

All classic teas can be roughly divided into a few main categories depending on how much the leaves are oxidised and how they are treated:

White tea

White tea is lightly oxidised tea where young buds and leaves are usually allowed to wither slowly and then dry, often with very gentle handling. Classic white tea comes from Fujian in China – for example Bai Hao Yin Zhen (Silver Needles) and Bai Mu Dan (White Peony).

The flavour is often mild, with notes of sweetness, hay, fruit and sometimes nuttiness. The younger the buds used, the finer and more delicate the character.

Yellow tea

Yellow tea is a rarer Chinese speciality with a strong historical link to the imperial court – the yellow colour is traditionally associated with the emperor. According to older texts, the method was developed to produce tea specifically for the emperor and his circle.

Technically, many yellow teas are close to green tea: the leaves are heated to stop oxidation, but then undergo an extra phase where they are allowed to “sweat” lightly wrapped under controlled heat and humidity. This yellowing phase gives a softer, rounder flavour and a slightly more yellow tone in both leaves and liquor.

At the same time, yellow tea is not a single style but a method that can be applied to different kinds of tea. Jun Shan Yin Zhen is, in its structure, very close to a white tea where whole buds are slowly allowed to yellow, while Huang Da Cha is a dark tea that in character is close to a highly oxidised oolong. What unites them is the yellowing step – not that they all behave like classic green teas.

Green tea

Green tea is tea where oxidation is stopped early by heating – either by pan-firing, oven-heating or steaming. The leaves retain their green colour and the flavour ranges from nutty and roasted (many Chinese teas) to more grassy, umami-rich teas (many Japanese).

The differences between green teas are large – roughly like the differences between various wines. The name by itself says very little about quality.

Read more in detail in our section: Green tea – from tea plant to cup »

Oolong / Wulong

Oolong teas are partially oxidised – somewhere between green and black tea. The degree of oxidation can vary significantly, from very light, floral oolongs to dark, heavily roasted cliff teas from Wu Yi.

Classic regions include Wu Yi in Fujian, Fenghuang (Phoenix Oolong), Anxi (Tie Guan Yin) and Taiwan. Oolong is a world of its own, with teas that can be infused many times and reveal new nuances with each steeping.

Black tea (Hong Cha)

What is called black tea in Europe is called red tea (Hong Cha) in China – the name refers to the reddish colour of the liquor. Here the leaves have been fully oxidised before drying.

Black tea is now produced in large quantities in China, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and parts of Africa. The style ranges from light, aromatic Darjeelings to powerful Assams and classic British breakfast blends.

Dark teas – Hei Cha and Pu-erh

Beyond “ordinary” black tea there is the category Hei Cha – dark teas – where the tea undergoes further ageing and sometimes true microbial fermentation. The most famous example is Pu-erh tea from Yunnan in China.

Pu-erh comes in two main styles: Sheng (raw/“green”) and Shu (ripe/“black”). The tea can be aged for many years and continue to develop in flavour.

For a more in-depth overview: Pu-erh tea – aged tea from Yunnan »

TEA AND HEALTH – A SHORT OVERVIEW

Tea has been drunk for centuries not only for its taste but also for its perceived effects on well-being. In recent decades, many studies have looked at tea’s components – such as polyphenols, caffeine and amino acids – in relation to different health markers.

Results vary between studies, and individual studies should be interpreted with caution. Tea can be seen as part of an otherwise balanced lifestyle – not as a quick “solution” in itself. We focus on clear origin, high quality and teas that are enjoyable to drink every day. Those who want to go deeper can explore medical review articles and current research.

STORING TEA – THE BASICS

Tea is an organic material and is affected by its surroundings. Poor storage quickly makes tea lose aroma and pick up unwanted smells. In general, tea should be protected from:

- Air – too much oxygen speeds up ageing and aroma loss.

- Light – UV light breaks down sensitive compounds.

- Moisture – risk of mould and unwanted fermentation.

- Foreign odours – tea behaves almost like a “sponge” for smells.

In practice this means storing tea in a tight, odour-free container, preferably filled as much as possible, in a cool, dry place protected from direct light. Green and white tea are most sensitive, followed by oolong and black tea.

Our resealable silver bags for premium teas work well as primary packaging – they protect against light, minimise air exchange and can be closed again after opening.

AGEING TEA – WHEN TIME IS PART OF THE STYLE

Most teas are best enjoyed relatively fresh, especially lighter green and white teas. But some teas are made for ageing – where time is part of the style:

- Pu-erh and other dark teas (Hei Cha)

- traditionally hard-roasted Wu Yi oolong

- certain aged oolongs and white teas

These teas can develop deeper, softer and more complex flavour profiles under controlled storage. The basic principles are dry air, protection from strong odours, no direct sunlight and stable temperature.

For detailed advice on storing Pu-erh, see: Pu-erh tea – ageing and development »

TEA GRADINGS – WHAT DO THEY MEAN?

Tea gradings are used in different ways in different traditions. They may describe leaf appearance and size, plucking standard (bud vs larger leaf) and in some cases also an internal quality level. How much a grading tells you about flavour therefore depends on the country and tea style.

Black teas from India, Sri Lanka and similar regions

For classic black teas from India, Sri Lanka and similar areas, the grading mainly describes how the leaves look – not directly whether the tea is good or not.

- D / Dust – very fine particles, almost powder; mostly used in teabags.

- Fannings – small leaf fragments, also common in teabags.

- BOP – Broken Orange Pekoe – broken leaves.

- FBOP, TGBOP, etc. – broken leaves with some buds.

- OP – Orange Pekoe – whole, longer leaves.

- FOP – Flowery Orange Pekoe – whole leaves with buds.

- TGFOP, FTGFOP, SFTGFOP – progressively higher proportion of tips and finer leaf standard.

Here, a higher leaf grade primarily means that leaf size and appearance are “finer”. But a tea with beautiful leaves can still be simple in flavour if origin, plucking, processing or storage are not at the same level.

Green, white and oolong teas – especially from China and Japan

For many green, white and oolong teas – especially from China and Japan – grading is more closely linked to plucking standard and raw material quality. Higher grades usually mean:

- higher proportion of buds and younger leaves

- more selective and labour-intensive plucking

- more even and carefully sorted raw material

This means that a higher grade in practice often coincides with higher quality in the cup – but it is still not an absolute guarantee. Different producers use their own grading systems and two teas with the same grade can differ significantly in style and level.

As a buyer, it is therefore wise to see grading as one clue among several: origin, harvest, producer, style and your own taste matter at least as much as the letters on the label.